Events

ARED Conference

The ARED team are hosting a conference at the University of Stirling, June 2-4 2025. Please visit our website for more information.

ARED Practitioner Workshop 2

31 May 2024

Gut Aiderbichl, Henndorf bei Saltzburg, Austria

This time around, the practitioner workshop will be held in Austria. Researchers from the Messerli Research Institute and the University of Stirling will be joined by:

- Marianne Wondrak, Gut Aiderbichl

- Simone Gräber & Elisabeth Sablik, Tierschutzombudsstelle Wien

- Alexandra Wischall, Tiere Helfen Leben

- Sandra Gatterer, Pferdegestütztes Coaching

- Helene Zacher, Demokratiezentrum Wien & Ariane Veit, ALICE project

- Sabrina Karl, Vier Pfoten

Schedule

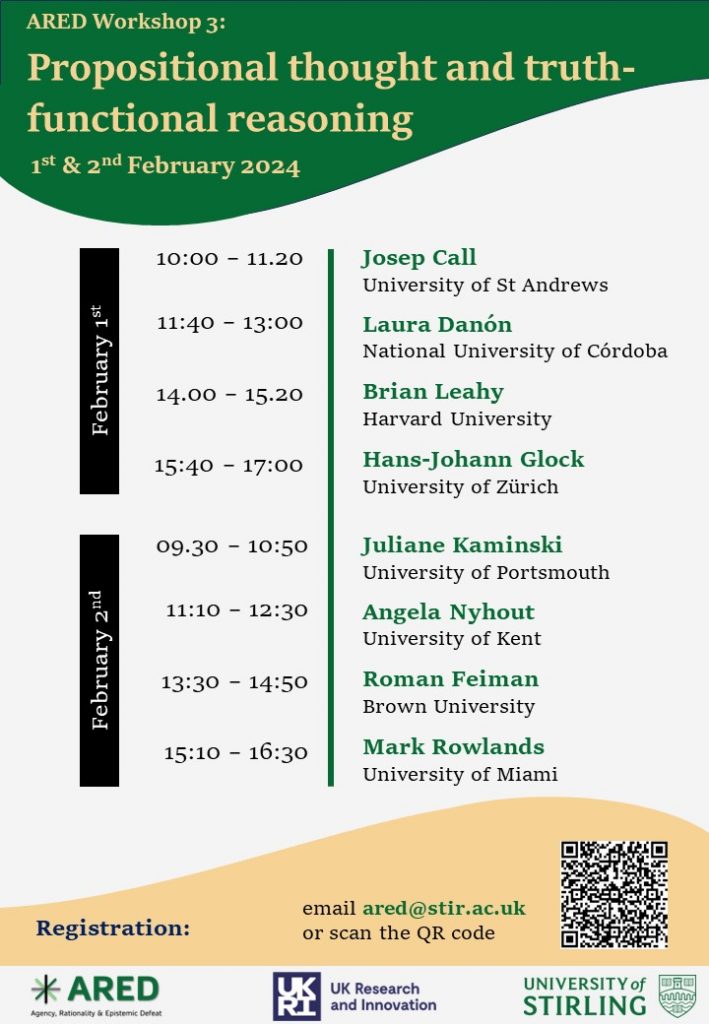

ARED Workshop 3:

Propositional thought and truth-functional reasoning

1 & 2 February 2024

University of Stirling

Despite widespread practice in cognitive and comparative psychology to ascribe beliefs and other propositional attitudes to very young children and non-human animals, the nature of such attitudes remains a matter of controversy. Some have suggested that they might involve imagistic or map-like representations rather than propositional ones. Others have emphasized the difficulty of individuating the concepts possessed and entertained by minimally verbal and non-verbal subjects and went on to question the accuracy and legitimacy of ascriptions of propositional attitudes to them. As truth-functional reasoning involves representational mechanism that go beyond the demonstrative-governed mechanisms characteristic of perception, the capacity for truth-functional reasoning is often taken to be a sign of propositional thought. Recent empirical research provides some evidence of truth-functional reasoning in non-human animals and young children, as the studies on children’s use of denial-negation and disjunctive syllogism in both animals and children illustrate. Nevertheless, in many cases explanations not involving propositional thought and deductive reasoning have been proposed by sceptics.

In the third ARED workshop we engage with the issue of propositional thought and ascriptions thereof in non-verbal and minimally verbal subjects, together with its relation to truth-functional reasoning.

Schedule

Update on schedule: Unfortunately, due to unforeseen circumstances the talk by Juliane Kaminski has been cancelled. The workshop on Friday, the 2nd of February will start at 11:10 with the talk by Angela Nyhout. We apologize for any inconvenience this change may cause.

Abstracts

University of St Andrews

Chrysippus’ dog and the origins of modal concepts

Since Chrysippus’s time, scholars have wondered about whether nonhuman animals are capable of making inferences, and if so, whether they are grounded on logical reasoning. Much of the empirical effort in comparative cognition has been devoted to distinguishing inferential from non-inferential processes based on associative or low-level general attentional processes. Much less research attention has been devoted to investigate the modal nature of inferences in nonhuman animals. In this talk, I will present a series of object search studies investigating whether primate inferences are probabilistic or deterministic. In other words, do primates merely consider possibilities or can they also conceive necessities? I will then connect this emerging body of work with the research on intuitive statistics and the prediction of past and future outcomes.

National University of Córdoba

Propositional Beliefs and Doxastic Revision in Great Apes

This presentation has two aims. Firstly, I will argue that we have empirical and philosophical reasons to defend that great apes have beliefs with a specific kind of intentional contents, which I will call “modest propositional contents”. These are contents composed of concepts of particulars and concepts of general properties that can be recombined in some ways to represent different states of affairs in a systematic and productive manner. Secondly, I will suggest that these animals can engage in first-order processes of doxastic revision, in which they reject some of their propositional beliefs and accept others based on reasons. This kind of belief revision does not involve capacities for second-order thinking or sophisticated semantic and epistemic concepts. However, if great apes are capable of first-order belief revision, then one can take them to be rational and normative animals.

Harvard University

Evidence that children appreciate possibilities emerges in parallel in language and behavior

When we speak, words like ‘maybe’ and ‘might’ can be used to mark a sentence as merely possible, as one member of a range of competing alternatives for a single reality. These words allow us to coherently describe incompatible possibilities in a single, coherent sentence. It’s incoherent to say that Jim is in Paris and Jim in Rome, but there’s nothing incoherent about saying that Jim might be in Paris and might be in Rome. Cognition has elements that perform this function as well, flagging propositions as merely possible, enabling us to store information about multiple incompatible possibilities in a coherent model that supports effective action. I call any element that has this function a “possibility concept”. How do possibility concepts support reasoning and decision-making, and how do they develop?

In this talk, I will show curious lapses in preschoolers’ decision-making when they are faced with multiple incompatible possibilities. These lapses indicate that they are not deploying possibility concepts. Then I will show that these lapses are related to language comprehension. Many children have mastered parts of the English modal auxiliary system by 36 months of age. But mastering the full system takes much longer; many 4-year-olds still have not mastered the full system. But those 4-year-olds who have mastered the full system do not show these curious lapses in their decision-making. Four-year-olds who have not yet mastered the auxiliary system show the same curious lapses as much younger children. These data prompt a challenging question: does learning to talk about possibilities play a role in the development of concepts for thinking about possibilities?

University of Zürich

Factual Perception in Animals—a Dog’s Breakfast?

There is an influential line of reasoning against the legitimacy of ascribing thought (beliefs, desires, intentions) to non-linguistic animals. This ‘lingualist master argument’ runs: no thought without concepts (concept thesis); no concepts without language (language thesis); therefore no thought without language (lingualist conclusion); but animals lack language (dumbness thesis); therefore no animal thought (differentialist conclusion).

This paper accepts the dumbness for the sake of argument and leaves aside the problematic credentials of concept and language thesis. Instead it pursues an independent argument against the possibility of animal thought denied by the differentialist conclusion. It runs as follows:

P1 The reaction of intelligent animals to their environment can only be explained by a capacity to perceive that p.

P2 If A perceives that p, then A knows or at least believes that p (depending on whether or not ‘perceives’ is used factively).

C1 Intelligent animals can know or believe that p.

C2 Intelligent animals can think that p.

The first part of my paper supports P1—that-ish or factual perception in animals–by ruling out alternative explanations of incontestable feats of perceptual learning (behaviourism, alternative representational formats, etc.).

The second part explains why it is important to support P1 not just by appealing to the (neuro-)physiology of perception but also to our established practice of ascribing thought on the basis of behavioural capacities.

The final part defends P2 by appeal to the principle that seeing is believing, taking account of objections invoking perceptual illusions. C2 stands, therefore. Given that the lingualist master argument is valid, this counts against concept thesis and/or language thesis.

University of Portsmouth

Through a dog’s eyes….

In recent decades, dogs have become one of the most popular animal species in comparative psychology. One reason for this is the unique evolutionary history of dogs. Through domestication, dogs have undergone morphological and behavioural changes that have adapted them to human life. The hypothesis is that dogs evolved to ‘understand’ humans. Here I discuss the extent to which dogs may have adapted in their cognitive and communicative abilities. I propose that as an adaptation to the dynamic social interactions between dogs and humans, traits exhibited by dogs create the illusion of human-like communication and emotion, and thereby the illusion of human-like understanding.

University of Kent

Where do counterfactuals come from?

In this talk, I will discuss what it takes for children to be able to think counterfactually, and where this ability might come from. To reason counterfactually, we compare the way things are to the way things could have been, requiring us to hold two representations of a situation in mind. In recent years, there has been intense interest in the development of this ability. There is substantial debate over when it develops – with our research indicating 4-year-olds think counterfactually, and others’ work suggesting it is not until late childhood or adolescence. Nevertheless, counterfactual thinking is commonly seen as a relatively late-developing ability. In the first part of the talk, I will present data from a wide range of tasks to examine the types of counterfactual representations children can reason with, and when they might deploy this ability spontaneously. The field currently lacks an explanation for how the ability to think counterfactually emerges. In the second part of the talk, I will therefore outline a mechanistic account of the development of counterfactual thinking, arguing that the experience of expectation violation is a developmental precursor and impetus for the development of mature counterfactual thinking.

Brown University

The development of negation in language and thought

Humans have the remarkable ability to understand and express an unbounded number of thoughts. You may have never heard the sentence, There are no bears on Mars, but you have no trouble understanding what it means, judging that it’s probably true, and inferring that if there are no bears on Mars, that means there are no brown bears there, no bear cubs, and no bears climbing Martian trees. An elegant explanation for these abilities is that the meanings of complex expressions derive from the meanings of their individual parts and the way these parts combine. While some words – like bears and Mars – provide the parts to be combined, logical words like no give instructions for how to combine them. That makes the acquisition of these words and the development of their meanings a window into the emergence of combinatorial language and thought.

Does learning words like no and not allow children to combine meanings in new ways — to negate them for the first time — or do these words merely label an operation that already existed in infant thought? Does each logical word (no, not) specify a unique way to combine content, or is there a narrower set of primitive operators (like the negation operation from first-order logic), that multiple words correspond to? I will describe sources of evidence from different populations that can help address these questions: data from children who are just on the cusp of learning these words, data from internationally adopted children learning English at an older age than typical infants, and data from adults whose language input is limited in order to simulate children’s language comprehension at different ages. I’ll argue that all of this evidence converges on the same conclusion: that a concept of negation is available for children to think with before they ever learn how to express it in words.

University of Miami

Animals, Concepts, and Beliefs

Can a (nonhuman) animal have beliefs? A well-known argument, championed by Davidson, Stich and others claims they cannot – or if they can, we cannot know what those beliefs are. Folk-psychological explanation – a way of understanding behavior that appeal to beliefs, desires, and other propositional attitude – cannot, therefore, be coherently employed in the case of animals. The argument turns on the relation between beliefs and concepts. Beliefs require concepts and concepts, in turn, requires networks of beliefs. An animal that lacks our network of beliefs also lacks our concepts, and there we cannot attribute to it beliefs that involve these concepts. This argument fails. Fundamentally, the problem it identifies is an anchoring problem. Our concepts are anchored to us whereas the concepts of other animals are anchored to them. There are apparatuses and strategies that allow us to address this kind of problem. This allows us to understand more accurately what we are doing when we explain an animal’s behavior in terms of beliefs and desires, and also how animals are able to engage in another staple of folk psychology: deductive reasoning.

ARED Practitioner Workshop 1

30 November 2023

Cottrell Building (C.2A87), University of Stirling

9.30am – 4.15pm

The ARED project team is delighted to announce that a practitioner workshop is in the works. Taking place on 30th November at the University of Stirling, the workshop will provide a platform for practitioners and researchers in the field of animal behaviour, animal minds and animal welfare to exchange insights and experiences related to the mental and cognitive lives of animals. Designed to bridge the gap between theory and practice, this workshop aims to foster knowledge exchange and promote meaningful collaboration.

Researchers from the University of Stirling and the Messerli Research Institute, Vienna, will be joined by five external organisations, each with vast practical experience in their respective fields. We are delighted to announce attendance from the following organisations:

If you would like to express your interest in attending or have any questions, please contact us at ared@stir.ac.uk.

Workshop Schedule

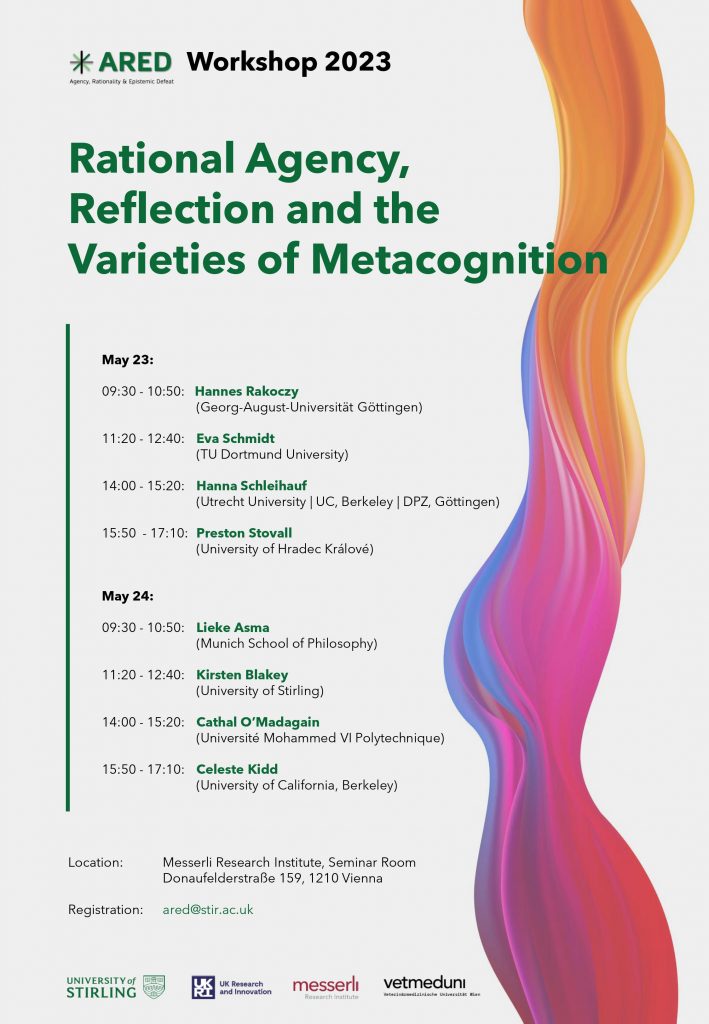

ARED Workshop 2:

Rational agency, reflection and the varieties of metacognition

23 & 24 May 2023

Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna.

One of the central questions in philosophical discussions on rational agency is what it takes to respond to reasons for belief and action. Some maintain that the capacity to critically assess one’s reasons is necessary, while others suggest that mere sensitivity to reasons is sufficient. Philosophers thus envisage two notions of rational agency: a reflective one seemingly limited to cognitively developed humans, and an unreflective one that may be within the reach of young children and non-human animals. The relation between the two is beginning to be explored. The empirical debate on metacognition offers a structural analogy with the distinction between object-level cognition and the metacognition involved in thoughts about other thoughts and ascriptions of mental states. Growing interest in so-called “procedural” metacognition is, at least in part, driven by the ambition to bridge the gap between the two.

In its second workshop, ARED continues to promote the dialogue between the philosophical and empirical study of the mind and rationality by bringing together researchers from different disciplines who are working on the broad themes of rational agency, reflection and metacognition.

Workshop Schedule

Abstracts

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

The Early Development of Taking and Giving Reasons

In this talk, I will present recent work from our lab on children’s early developing capacities for taking and giving reasons. In the first part, focusing on taking reasons, I will review studies on children’s belief-revision. These studies show that from around age 4, at the latest, children engage in selective and rational belief-revision in response to other agents’ advice, and in this context do take into account arguments given by others – but only if they are epistemically appropriate and convincing. The second part focuses on the development of giving reasons. Here, I will report new studies on children’s developing meta-cognition. What these studies suggest is that children reveal meta-cognitive competence much earlier once meta-cognitive judgments are not elicited in solitary conditions but as part of giving reasons towards others. The implications of these findings for social origins theories of meta-cognition and argumentation are discussed.

TU Dortmund University

The Reasons of AI Systems

This talk connects the fields of philosophy of action and of explainable artificial intelligence (AI). I investigate, first, whether it can ever be appropriate to explain the outputs of AI systems by appeal to practical reasons of these systems. I argue that this can indeed be fitting. Second, I examine what the resulting reason explanations would have to look like. I show that different kinds of reason explanations of the outputs of AI systems can be appropriate depending on context.

Utrecht University | University of California, Berkeley | DPZ, Göttingen

Seeking, Evaluating, and Sharing Information – An Evolutionary and Cross-cultural Perspective

Effective decision-making relies on a rational agent’s ability to seek out, evaluate, and act upon relevant information, as well as to share that information with collaborators as needed. In this presentation, I will report a series of empirical findings examining these domains, drawing on data from studies involving children from diverse cultural backgrounds, as well as our closest evolutionary relatives, chimpanzees. Specifically, I will first present evidence indicating that young children apply more efficient information-seeking strategies than chimpanzees. Next, I will describe a set of studies investigating children’s developing ability to evaluate and integrate information from diverse sources, and how this development is influenced by culture. Finally, I will present a set of studies exploring situations that trigger children to share information about the reasons underlying their own beliefs. Taken together, these findings shed light on the complex interplay between rational agency, and searching, evaluating, and sharing information, and provide insights into the factors that support effective decision-making in both children and non-human primates.

University of Hradec Králové

Reflective Single-Minded Agency as the Font of the Transformative Power of Rationality

According to additive theories of rationality, the perceptual and volitional activities of non-rational animals do not differ in kind from those of the rational animal: the capacity for rational thought adds to, but does not change, the perceptual-motor capacities we share with non-rational animals. According to transformative theories of rationality, the capacity to reason affects those abilities in ways that mark a qualitative difference in their operations.

Using the resources of modal logic, I argue for a transformative theory of rationality. In order to model the distinction between the strong and weak deontic modalities (“ought” versus “may”), I introduce a notion of single-minded practical cognition, and I gloss this notion in terms of physiological capacities for higher-order executive functioning. My central claim is that the capacity for self-government, brought off in the exercise of single-minded agency, underlies our grip on reason’s commands understood as such, and this grip reworks the way our habitual perceptual-motor behavior operates. To plan single-mindedly is to practically classify acts according to genus/species relations, as means suitable to different ends. But the explicit consideration of genus/species relations presupposes a reflective ability to think about thought itself. Consequently, it is only when the self-government made possible by single-minded agency is exercised within a linguistic community whose members direct that capacity at their own speech – by choosing single-mindedly concerning linguistic acts – that a properly discursive or reflectively self-governing cognition is on the scene.

In such a linguistic community, the initially domain-specific and practical grasp of genus/species relations, manifest in single-minded agency, can then become a mechanism of cognitive classification along which the reflective study of genus/species relations hones the domain-general classificatory abilities that accompany adult human language use. In this fashion, even our instinctive behaviors may be transformed: we might cease to respond to events simply as (e.g.) fearful or enraging, and begin to treat them as opportunities for restraint or courage.

Munich School of Philosophy

Reasons as Actions and Faulty Practical Reasoning

One of the central questions in the philosophy of action is what motivating reasons, those reasons that the agent takes to justify her action and for which she actually acts, exactly are. Most philosophers either take them to be psychological states, such as (combinations of) beliefs and desires (e.g., Davidson, 1963), or maintain that motivating reasons are facts, the things that the agent believes (e.g., Alvarez, 2009; Dancy, 2000). In recent years, however, in line with G. E. M. Anscombe’s theory of action, a growing number of philosophers have argued that motivating reasons are actions at a higher level of description (Anscombe, 1963, see also Singh, 2020; Thompson, 2008; Wiland, 2012). The reason for which I am cutting an onion, for example, is that I am making a curry. That I am making a curry both justifies and explains cutting an onion.

In this paper, I will first defend and explain the view of motivating reasons as actions at a higher level of description. I argue that both psychologism and factualism suffer from deviant causal chains, and that factualism does not provide a complete explanation of why the agent acts as she does. After that, I apply the insights from the reasons-as-actions account to explain what may go wrong when people display implicit bias in considered decisions, for example when they have to select a police chief from two candidates and are, unconsciously and unintentionally, influenced by the gender of the candidates (Uhlmann & Cohen, 2005). I argue, in line with Sandis (2015) but in a different sense, that agents displaying bias in considered decisions are not wrong about the reason for which they act. After all, they know that they should be selecting the best candidate for the job as police chief, and that is what they are doing (or, trying to do). Different from Sandis (2015), however, I do maintain that these studies demonstrate a fault in our practical reasoning: the subjects are using, without being aware of doing so, irrelevant information to make up their minds (see Ford, 2016). The result is an account of how we can be biased in action.

University of Stirling

Reimagining Metacognition: The Transition from Unreflective to Basic Reflective Thinking

The distinction between object level cognition and metacognition has been the subject of fierce debate over the past few decades. Whereas metarepresentationalists believe metacognition only occurs when a mental representation represents another mental representation at the personal level (Carruthers, 2018; Perner, 2012), proceduralists argue that metacognition can occur in non-verbal subjects through the monitoring and control of cognitive processes, regardless of whether it involves metarepresentation (Proust, 2019). Both approaches have focussed on the nature of metacognitive states but have said little about the transition from the object level to the meta-level. I will outline an alternative approach which promises to explain the transition from the object level to the meta-level, while vindicating some of the main insights of the two rival views, focussing on conscious thought but also allowing for non-metarepresentational forms of metacognition. This novel approach suggests that the cognition/metacognition opposition may be characterised—at least when the focus is on conscious thought—as the one between unreflective and reflective responsiveness to evidence or reasons.

Universite Mohammed VI Polytechnique

Ways of Reasoning in Humans and Other Animals

The ability to reason – that is, to keep track of and evaluate the reasons for our actions and beliefs – is surely the origin of much of human invention and culture. It has also long been considered a human-unique capacity. But experimental evidence now indicates that other animals keep track of, and even double-check, the reasons for their actions and decisions. This suggests that humans are not the only animals that forage in the garden of reasons. The manner in which humans reason, however, may well be unique. Particularly, humans invoke others’ reasons in their own decision-making to a degree that sets apart the human way of reasoning, both in its ‘tacit’ and ‘articulated’ forms. I propose here that this distinctively social form of reasoning is what underlies the cross-generational refinement of innovations and tools characteristic of human culture, sometimes called ‘cumulative culture’, providing a novel answer to the question why we give and ask for reasons. On the other hand, allowing that reasoning per se is not a uniquely human achievement allows us to explain some remarkable abilities in our nearest evolutionary cousins, and allows for a perhaps overall simpler account of its evolutionary origins.

University of California, Berkeley

The role of uncertainty in guiding learning and belief formation

The talk will discuss the role of uncertainty in guiding the formation of beliefs and exploratory behavior throughout the lifespan, starting in infancy and continuing through adulthood. I will discuss both implicit and overt representations of uncertainty, and empirical evidence from our lab on how they drive attention and information-seeking behaviors in infant and adult humans, and also non-human primates. I will discuss empirical work exploring how humans form uncertainty as children and adults, and argue for the importance of feedback in determining human certainty. We will discuss how certainty diminishes curiosity, and runs the risk of leaving learners with the wrong idea under particular circumstances. Finally, I will discuss recent efforts in the lab to design interventions and environments that encourage uncertainty and promote healthy skepticism.

ARED Workshop 1:

Epistemic agency and rational belief-revision

17-19 January 2022

2pm – 7pm (GMT)

This workshop will be held in a hybrid format at the University of Stirling and on Zoom.

The first ARED workshop focussed on epistemic agency and rational belief-revision broadly construed.

In the interest of fostering interdisciplinary exchange, speakers pitched their presentations in a way that was accessible to non-specialists.

Schedule

Monday January 17: starting time 1:50 pm GMT (2:50 pm CET, 5:50 am PST, 8:50 am EST)

1:50 – 2:00 Welcome

2:00 – 3:20 Agnes Kovacs (CEU): Flexible update and revision of others’ mental states in early development

3:40 – 5:00 Josef Perner (Salzburg): Mental Files Join Teleology

5:20 – 7:00 Hannah Ginsborg (Berkeley): Non-rational agency in concept-acquisition and language-learning

Tuesday January 18: starting time 3:40 pm GMT (4:40pm CET, 7:40am PST, 10:40am EST)

3:40 – 5:00 Kirsten Blakey, Giacomo Melis, Eva Rafetseder & Zsófia Virányi (Stirling): In search of reflective thinking in non-linguistic agents

5:20 – 7:00 Matthew Boyle (Chicago): Reflection and rationality

Wednesday January 19: starting time 2pm GMT (3pm CET, 6am PST, 9am EST)

2:00 – 3:20 Ludwig Huber (Messerli, Vienna): The concept of seeing in dogs

3:40 – 5:00 Christoph Völter (Messerli, Vienna): Do nonhuman animals seek explanations?

5:20 – 7:00 Hilary Kornblith (Amherst): Doubts about epistemic agency

Abstracts

Matthew Boyle

University of Chicago

Reflection and Rationality

The topic of this paper will be reflection: the activity by which (I claim) we can move from an implicit, non-conceptualized awareness of aspects of our own mental state to an explicit, conceptual recognition of these aspects. My aim will be, first, to raise and address some puzzles about the nature of this activity, and then to consider its relation to our rationality, understood as our general capacity to consider propositional questions and assess the grounds for different answers to them. A venerable philosophical tradition sees a close connection between our capacity for reflection and our general rationality. But why should our capacity to reflect on our own mental states make a difference to the general character of our cognition, rather than just enabling us to think about a special topic, namely our own mental states? I’ll argue that, in order to understand the link between rationality and reflection, we must first appreciate that reflection is capable, not just of providing us with information about our first-order mental states, but of transforming these first-order states themselves.

Hannah Ginsborg

University of California, Berkeley

Non-rational agency in concept-acquisition and language-learning

Drawing on findings in developmental psychology, I identify a distinctive kind of agency which is manifested in the sorting activities and early language use of human children. The exercise of this agency is manifested in the child’s recognition of her behavior as normatively governed, where this recognition is primitive in the sense that it does not depend on her grasping reasons for her behavior. I suggest that epistemic agency, understood as requiring the capacity to appreciate reasons for one’s beliefs, depends on this more primitive form of agency. The appreciation of reasons for belief, at least in paradigmatic cases, presupposes the possession of concepts and, relatedly, the capacity to use words with determinate meanings. But these in turn, I argue, depend on the primitive recognition of normativity in one’s sorting behavior and use of words.

Ludwig Huber

Messerli Research Institute, Vienna

The concept of seeing in dogs

A particularly interesting question within the larger framework of Theory of Mind is whether non-human animals can acquire or form the concept of “seeing”. More specifically, it remains an open question whether any non-human animal can attribute the concept “seeing” without relying on behavioural cues. In this talk I will present studies showing that dogs perform successfully in several tasks related to this ability. Starting with gaze detection, gaze following into distant space and geometrical gaze following I will then discuss the ability to decide about the visual access of others. Surprisingly, dogs have been outstanding in solving many of these tasks instantly and reliably across a large number of variations, including stealing in the dark and guesser/knower tasks. Still, the question remains if subjects had to integrate observable features from the others’ current or past behaviors, and might have based their decisions solely on their own rather than the others’ perspective. Recently we confronted dogs with a change of location task in which subjects have to decide where to go after witnessing a misleading suggestion by an informant who held either a true or false belief about the location of food. Although responding differently than great apes, dogs made this distinction, suggesting that they decided about what others have or have not seen, rather than what they themselves have seen. Taken together, it is difficult to explain these findings on the basis of the acquisition of associative rules rather than a concept of “seeing” and perspective taking. I will therefore suggest that dogs possess the perceptual precursors (or ‘secondary representations’) to mind-reading and discuss why they might have them.

Hilary Kornblith

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Doubts about epistemic agency

The notion of epistemic agency has come to play a very large role in contemporary work in epistemology. I myself, however, have some real doubts about whether there is any such thing. Some defend the existence of epistemic agency on the basis of phenomenological considerations, but I argue here that closer attention to the phenomenology of belief acquisition does not support any such claim to agency. Others defend appeals to epistemic agency in order to defend the normativity of epistemology, but I argue that all the normativity which epistemology needs requires no help from epistemic agency. Still others appeal to epistemic agency to make sense of the phenomenon of doxastic deliberation, but we can make better sense of such deliberation, I argue, without any appeal to epistemic agency. It is not at all clear, as I argue here, that there is such a thing as epistemic agency.

Josef Perner

University of Salzburg

Mental Files Join Teleology

I’ll give an outline of teleology as the basis of our folk psychology; an alternative to theory of mind (theory theory) and simulation as model of how we explain and predict behaviour. Teleology assumes that we act for objective reasons as public facts. The mind plays no role except to account for error cases (e.g., false belief), where subjective reasons play a role. Then teleology needs to be applied within the agent’s subjective perspective. Recanati (2012) suggested that perspectives can be captured in mental files theory by vicarious files. Regular files are the subject’s own representations of particulars (objects). They track their referent over time to collect information. Vicarious files are indexed to another person and are used vicariously for the other person’s regular file of the same referent. They are used like regular files but subject to specified conditions of storing and later using information. I illustrate how this can account for mistaken actions when the files implement teleology but not a theory of mind or simulation.

Kirsten Blakey & Giacomo Melis

(Eva Rafetseder & Zsófia Virányi)

University of Stirling

In search of reflective thinking in non-linguistic agents: an outline of interdisciplinary work in progress

In theorizing about epistemic rationality and agency, it is common to distinguish between reflective and unreflective responsiveness to reasons or evidence. It is also common to associate the reflective notion to the capacity of answering requests of reasons for one’s beliefs, and to the ability to formulate thoughts about other thoughts. Many have individuated the roots of epistemic agency in reflective responsiveness to evidence and have endorsed a view in which only subjects with developed linguistic skills and who are capable of explicit metacognition may properly be described as epistemic—or, more broadly, rational—agents. In the first part of the presentation, we explore an alternative framework whereby the root of epistemic agency resides in belief-revision and management, while a basic form of reflective thinking is already at work in the capacity to respond to a specific type of counterevidence: undermining defeaters suggesting that the evidence is misleading. In our picture, subjects unable to formulate thoughts about other thoughts or answer questions may be capable of reflective thinking. Having outlined the framework, in the second part of the presentation we illustrate the structure of an experiment aimed at testing whether pre-verbal children, dogs, and pigs may be able to respond to the type of counterevidence mentioned.

Christoph Völter

Messerli Research Institute, Vienna

Do nonhuman animals seek explanations?

Human children have been famously characterized as “scientists in the crib” because they actively seek information about the world to fill gaps in their knowledge (Gopnik et al., 1999). What about nonhuman animals? In this talk, I will present comparative cognitive research, mostly with nonhuman great apes, focusing on the question whether they can draw causal inferences, monitor their own knowledge states and seek information to actively fill gaps in their knowledge. Even though there is some evidence for these abilities, I will argue that more research is needed to conclusively answer the question whether we share the drive to seek explanations about the world with other species.

Ágnes Kovacs

Central European University

Flexible update and revision of others’ mental states in early development

Human behavior is guided by a set of mental states that we assume must form a coherent system. For instance, two agents can hold mutually incompatible beliefs or goals, but a single agent is unlikely to do so. However, an agent can unexpectedly change her mind (first aiming for “p” and then for “not-p”) or revise her beliefs given new evidence, requiring the observer to flexibly update these attributed mental states. First, we will present evidence that coherence is intuitively used to set the boundaries between other minds already in infancy. Second, we will present studies targeting flexible third person belief update and revision in infants, children and adults.